Sleepless, with Annabel Abbs

An author talk in Steyning, about discovering the power of the night self.

The corner of Sussex that I call home is rife with interesting events. I spent too much of my life going “oh, that looks interesting” when I spot something on a poster or a flyer — and then never going to the event. Well, last week I finally did so. I saw that The Steyning Bookshop were putting on a talk by Annabel Abbs, author of one of my favourite books from the last few years: Windswept: Why Women Walk. That book was a beautiful mix of insights into walking, which I can identify with, and the particular challenges women face, which is not something I have an intuitive understanding of.

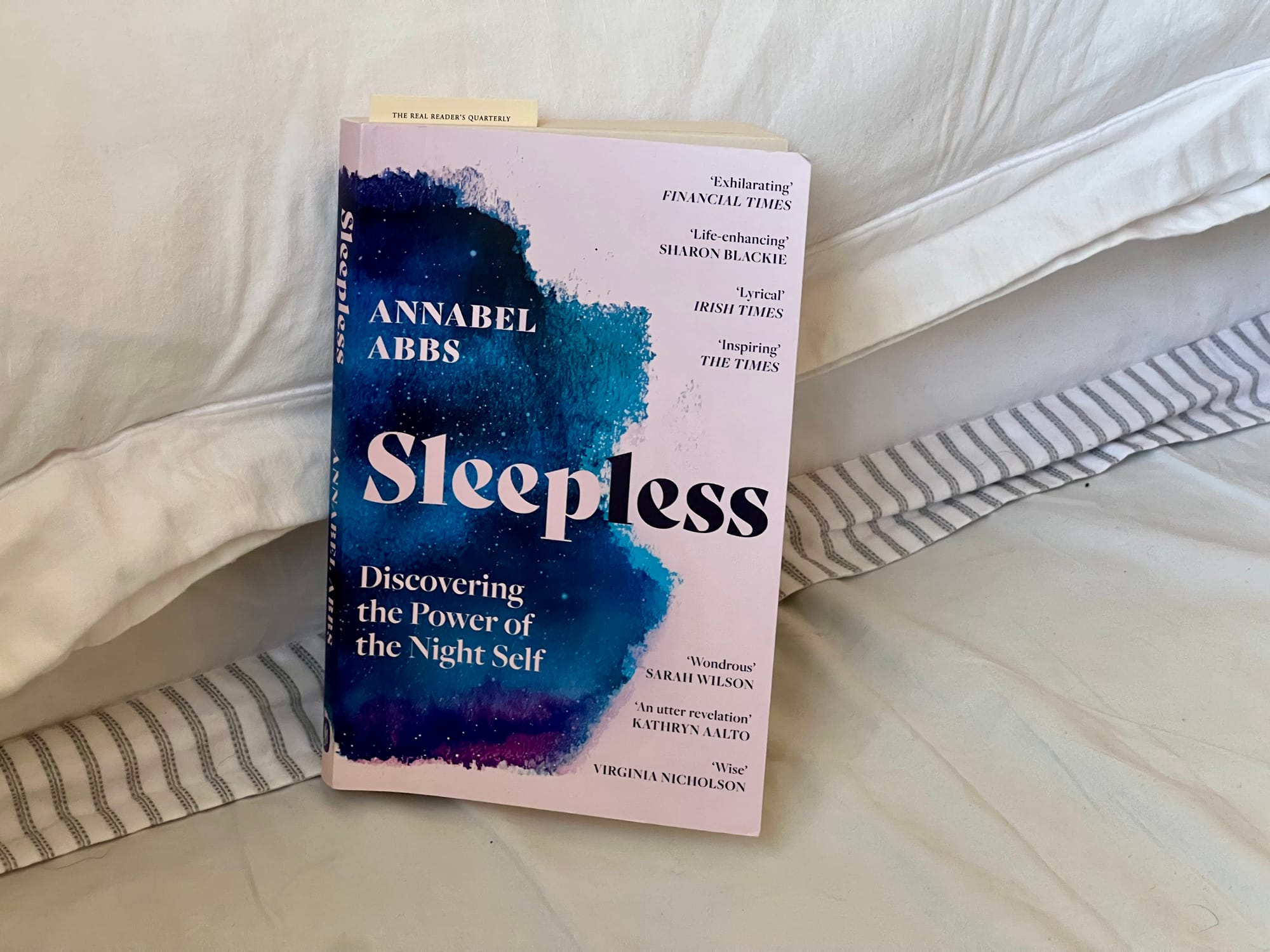

Given that I’ve been fighting my own battles with insomnia this year, her new book Sleepless seemed like something I’d find interesting. And so, I legged it out of City St George’s on a Wednesday evening, to make it back to Sussex and the Steyning Methodist Church in time.

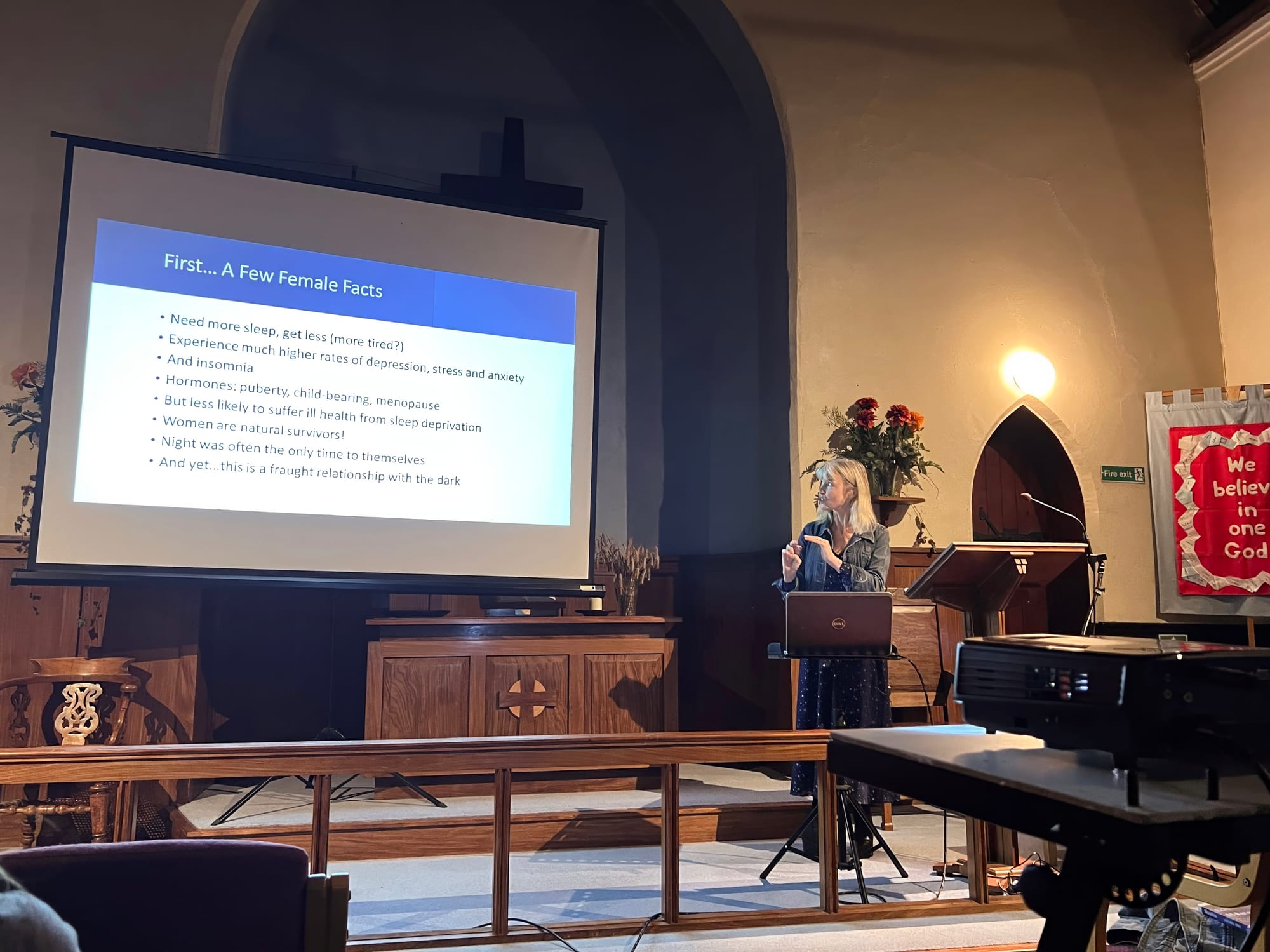

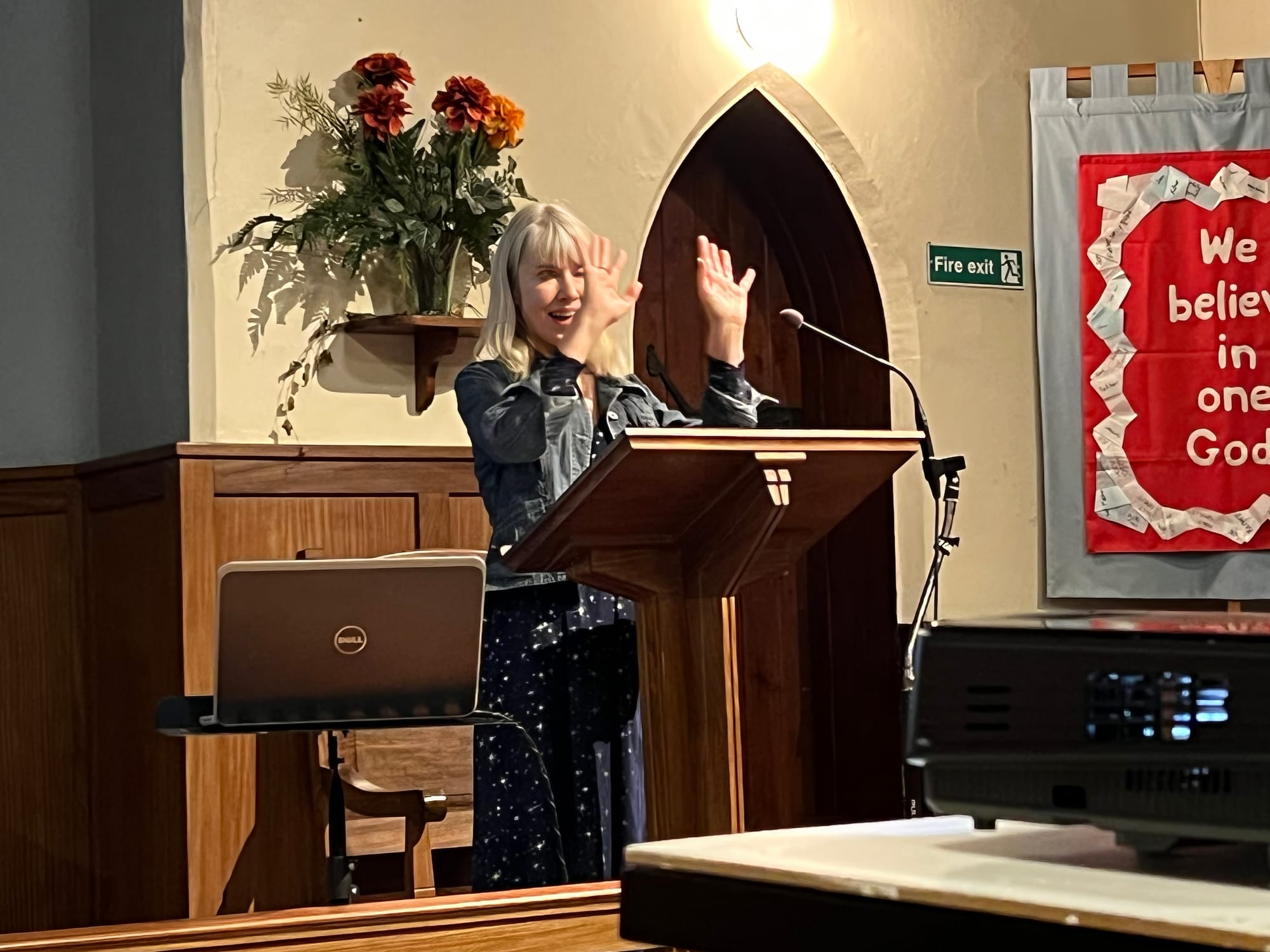

Annabel was clearly prepared — she had a series of challenges for us to discern which pieces of art and writing were produced at night, and which during the day. The audience were, on the whole, pretty good at it. But it immediately opened up the idea that night-time creativity might look very different from day-time work. And she went on to explore why that might be the case.

The rhythm of her talk was much like that of the book — which I’m still in the midst of reading — examples drawn from notable and less notable figures of the past, followed by an exploration of the science behind these discoveries. Our brains, indeed our entire physiology, functions very differently at night. In particular, our prefrontal cortex, the seat of rationality and control, loses its grip, and we become rebellious and wild, in idea, act and art.

This is, at its heart, an intriguing idea. When I was younger, I was much more of a night owl by nature. In particular, I did much of my best writing for White Wolf’s original World of Darkness line in the wee small hours of the night. Perhaps it shouldn’t be a surprise that my night self, as Annabel terms it, was a better fit for the Gothic Punk milieu I was writing in. Property journalist by day, personal horror game writer by night; two selves doing different creative endeavours.

The power of insomnia

Somewhat ironically, though, she attributes the trigger of insomnia and thus greater access to this night self to bereavement. For me, at least, bereavement — this loss of my father over two decades ago — spurred a burst of creativity, followed by a retreat from the night and the art of darkness. When my own life became more difficult, with my Mum also developing cancer, spending my creative and gaming time in a setting that dwelled on darkness lost much of its appeal.

That said, many of the examples of people who treated their insomnia as an opportunity rather than a problem to be solved were of those who had struggled with insomnia on and off in their life. The bereavement trigger — which Annabel herself had experienced — is far from universal. And, as she pointed out, the standard model of seven to eight hours a night at approximately the same time for most folks is a very recent construct.

Historically, people slept differing amounts at different times of the year, and often had two sleeps, with a period of wakefulness in the night. Even the full moon would sometimes provoke greater periods of both wakefulness and activity, as the greater light allowed work to continue for longer. We’ve let ourselves be persuaded that a particular pattern of sleep is the only valuable one, because that suits an industrialised society.

But it may not suit all endeavours.

Against the sleep industrial complex

Her message, in as much as there was a clear one, is that maybe fighting insomnia is not always the way to go. As she puts it early in the book:

And it struck me then that my decision to forgo sleeping pills, to desist the call of my usual trove of sleep aids, was my first act of disobedience. My first heretical idea in an age when a ballooning billion-dollar sleep industry has us in its anxious clutches. When eight hours of unbroken shut-eye - perfectly apportioned into deep and dream sleep - is considered a universal panacea.

Thankfully, my own sleeplessness has abated. But, should it return, I suspect I’ll explore some of these ideas. Trying to cosh myself into sleep with mindfulness techniques and audiobooks didn’t work last time. So, what do I have to lose by exploring creativity in the dark of the night?

So far, as I work my way through the book, the only thing that gives me any cause for concern is that men’s health is more severely affected by sleeplessness than women’s. But if I’m already suffering the health risk, why not make something of it?